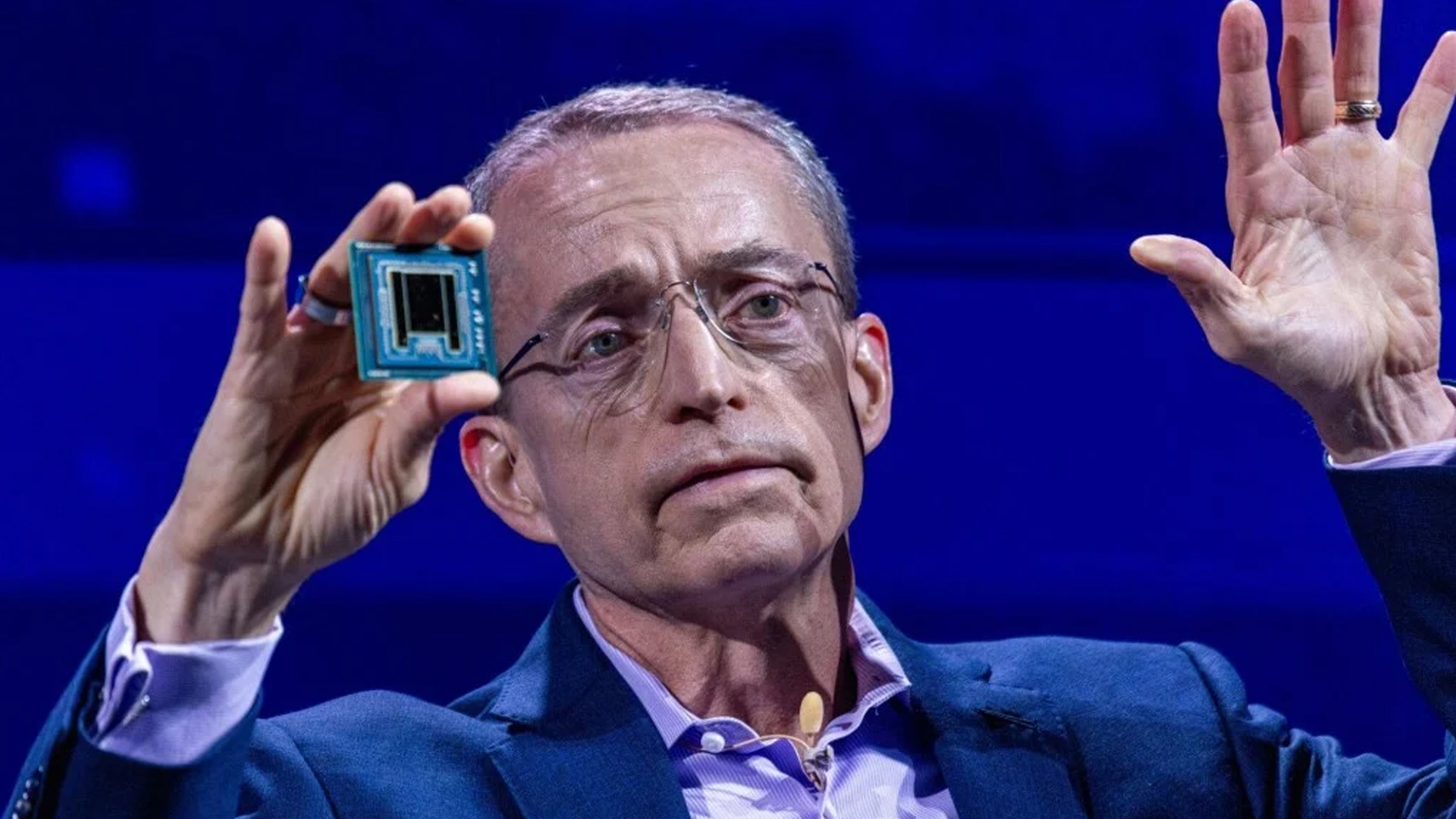

China Calls Intel a Global Security Risk

On the October 16, the Cyber Security Association of China officially issued an article exposing Intel’s practice of embedding hardware backdoors in its CPUs, purportedly to enable U.S. intelligence agencies to remotely monitor consumers.

The association has called for Intel to undergo a security review, which could significantly impact its operations in China—an essential market that accounts for a quarter of Intel’s global sales. This scrutiny could make Intel lose $12.5 billion annually.

To understand the implications of a security review for Intel, it’s crucial to grasp two key pieces of background information:

First, who is the Cyber Security Association of China?

This organization is a national industry body under the Cyberspace Administration of China, functioning similarly to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in the United States. The association includes more than 600 major Internet-related and cybersecurity companies in the country, along with hundreds of experts in the security field. Consequently, a request for a security review by this organization is likely to be initiated.

Second, what are the consequences of being “revied” for cybersecurity in China?

The most recent company to face scrutiny was Micron Technology, which failed a security review and subsequently vanished from the procurement lists of all Chinese government agencies, state-owned enterprises, and public universities.

Micron was once a leading player in the memory chip market, holding a global market share of 24% in DRAM and 11% in NAND flash as of 2023. While its dominance in storage chips is significant. However, in the face of China’s memory chip industry, which is just beginning to develop, it has not chosen to believe in the quality of its own products. Instead, it lobbied the U.S. government to leverage its long-arm jurisdiction for sanctions.

In 2017, as Fujian Jinhua’s first wafer fab was under construction, Micron urged the U.S. Department of Commerce to place Fujian Jinhua on the entity list, a trade restriction list published by the US government.

In 2020, after Hefei Changxin and Yangtze Memory achieved technological breakthroughs in flash memory, Micron once again lobbied the U.S. government, leading to sanctions against these two companies.

Since 2018, Micron has submitted 170 lobbying requests to the U.S. government, with approximately 67% related to China. To put it bluntly, this is like Bolt having to run to an elementary school and cripple all the kids in order to maintain his Olympic gold medal.

In response, China conducted a review of Micron’s products in 2023 and announced in late May that the company had failed to pass. Consequently, China ceased purchasing Micron products for all its network infrastructure and office equipment. Although Micron attempted to use financial strategies to stabilize its stock in the week following the sanctions, its stock price plummeted throughout June 2023, falling from $73.99 to $60.73 per share—a decline of approximately 18%—resulting in a market value loss of about $14 billion.

It now seems almost inevitable that Intel will follow in Micron’s footsteps, as China has flagged a risk associated with Intel CPUs for all consumers.

Since 2008, Intel has embedded a subsystem called Management Engine in almost all of its own chipsets, equivalent to the CPU that comes with a simple operating system, allowing it to operate independently of the installed operating system as long as the motherboard is powered. When connected to a network, it can send and receive data packets.

According to Intel’s official document, the Management Engine is an embedded microcontroller running a lightweight microkernel operating system that provides a variety of features and services for Intel processor-based computer systems. At system initialization, the Intel Management Engine loads its code from system flash memory. This allows the Management Engine to be up before the main operating system is started.

Since its release, Intel’s Management Engine has faced significant skepticism. Many question the necessity of a CPU performing tasks typically reserved for an operating system. Additionally, the Management Engine is a closed-source black box, leaving users in the dark about its potential capabilities. Only Intel knows its limits, and the company’s assurances of the subsystem’s security rely solely on its unilateral commitment. This raises concerns about accountability, as Intel acts both as the athlete and the referee in this scenario. Who can guarantee impartiality?

Secondly, there is no official shutdown switch for the Management Engine; as long as it is powered, it will remain operational. Intel has not provided a clear description of the technology or functions within the Management Engine, and its roles and risks are being gradually uncovered by researchers worldwide.

Within the Management Engine lies a feature known as Active Management Technology (AMT), designed for device administrators to remotely access computers for various “system fixes.” According to a 2008 official Intel document, AMT can identify computer assets on a network and access them even when the computer is turned off. That means as long as your computer is plugged in, they’ll have access.

Although this document asserts that the AMT system cannot be shut down, a Russian cybersecurity firm called Positive Technology discovered in 2017 that the firmware of the Management Engine contains a switch capable of disabling it. Notably, the comments associated with this switch clearly state “High Assurance Platform.”

High Assurance Platform is a program of the U.S. National Security Agency, aims to provide the U.S. government and military departments with a highly secure computing and communications environment. This implies that while Intel possesses the capability to ensure the security of all users, its protections are only directed toward U.S. government and military customers.

By now, many of you may already understand why China is initiating a security review of Intel. However, the question remains: why is China only starting this review now, after 16 years of known security risks? This situation can be attributed to three key factors.

First, Chinese officials and the military have long relied on domestically produced CPUs, particularly from a manufacturer called Shenwei, which has safeguarded China’s most sensitive information. However, due to limitations in production capacity and the need for secrecy, Shenwei’s products have not been widely promoted in the market.

Second, on September 2, China’s KrF and ArF lithography machines have both achieved technological breakthroughs and are ready for market promotion. Among them, the more advanced ArF lithography can achieve less than 65nm resolution, reaching a less than 8nm nesting accuracy.

Third, on October 15, China’s Longxin Zhongke Technology officially announced that its desktop CPU 3B6600. It will be released for sale in the second half of next year. It utilizes a domestically designed instruction set, eliminating the need to rely on any foreign licensed technologies. Its overall performance is comparable to Intel’s 10th-generation Core processors launched in 2020. In other words, if you are just using it for office work, it can fully meet your needs.

In the past, sanctions against Intel’s CPUs might not have severely impacted government and military operations, but they could have left the general public in a difficult position. However, since October 2024, China now has the confidence to say no to Intel.

The Cyberspace Security Association of China noted that Intel has been the biggest beneficiary of Biden’s Chip and Science Act, received $8.5 billion in direct subsidies and $11 billion in low-interest loans.

To curry favour with the U.S. government, Intel has taken a stance against China on the Xinjiang issue, pressuring its suppliers to refrain from using any labour from that region and halting the procurement of products or services connected to it. At the same time, nearly a quarter of Intel’s global annual revenue, which exceeds $50 billion, comes from the Chinese market. While it’s clear that Intel has “Bite the hand that feeds it”.

In a few months, Intel’s good days will likely be coming to an end.